Advocates hail centrally planned

smart cities as the future, but others,

including Ratti, insist a bottom-up ap-

proach is more sustainable. Amsterdam,

Singapore, and Portland are frequently

held up as good examples of existing

cities getting smarter. The Dutch capital

has set up the Amsterdam Smart City

initiative, essentially a platform whereby

companies, authorities, research institu-

tions, and ordinary citizens can come

together to test and develop innovative

products and services.

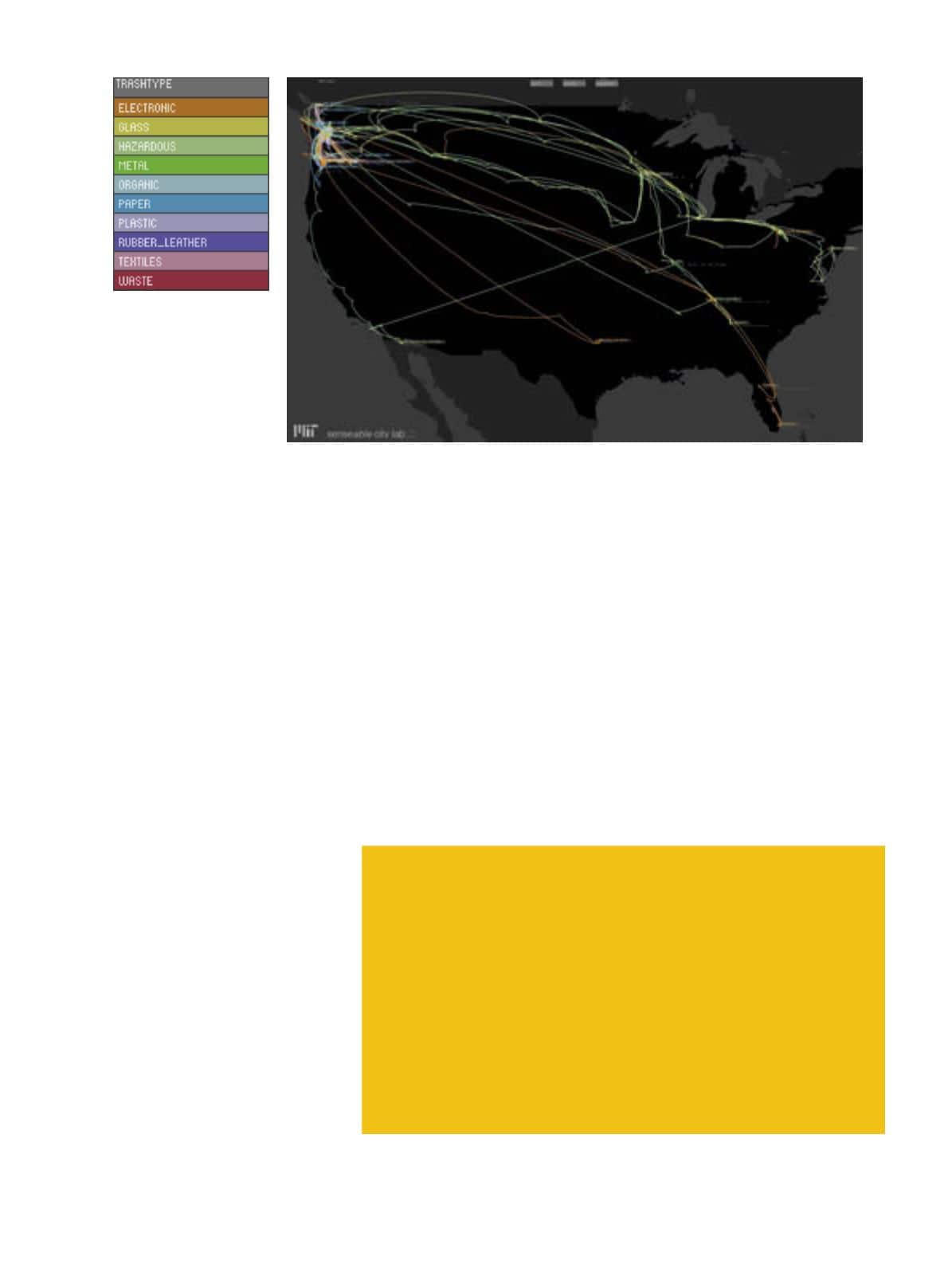

Changing behavior

Ratti and his team at MIT have

conducted a number of studies aimed

at mapping the pulse of a city in order

to gain unique information about

how a city behaves. “We can then

use this information to change the

city – through planning or through

the response of citizens to this infor-

mation,” he explains. In one project,

Ratti’s team tagged 3,000 items of

garbage thrown out by 500 residents

in Seattle and tracked each item to its

final resting place. At the end of the

project, one of the participants said

seeing where the items he threw out

ended up had had a profound impact

on his behavior, convincing him to cut

down on the amount of solid waste his

household produced.

As far afield as Edinburgh, New York,

and Winnipeg, smart information

boards at bus and subway stops give

travelers real-time updates on when

the next bus or train is due. Research

shows these boards encourage

people to use public transport,

cutting down on congestion and air

pollution. Other innovations include

a device which integrates with your

smartphone so that you can switch

on the heating or air conditioning

in your home as you begin your

commute, thereby reducing energy

wastage and ensuring your home

is just the right temperature for

your return. In Portland, Oregon,

developers are working on a simple

sensor that would send data to a

command center and then update

an application on your smartphone,

directing drivers to the nearest

available parking space which would

have been saved for them.

Smart picks from around the world

Too smart

Few people would object to innovations

which save them time and money, but

is there a danger that our cities become

too smart, relying too heavily on tech-

nology? The 2012 Olympics brought

huge fears for Londoners of the possibili-

ty of a cyber-terrorist attack which could

have brought the whole city to a halt.

Meanwhile in New York City, in Pollalis’s

view America’s most efficient city due to

its density, large swathes of the urban

metropolis were left without power for

weeks and in some cases months after

Hurricane Sandy hit in October 2012.

Pollalis believes that none of the

risks are insurmountable, provided the

technology is “used prudently, has been

extensively tested, and is well designed,

with a proper back-up system.”

Visions of tomorrow

So what will the future look like? “From

the physical point of view it will not

be too different from today. As at the

time of Romans 2000 years ago, we

still need and will need horizontal

planes for living, facades to protect us

from the outdoor environment, and so

on,” says Ratti. “But the activities that

humans will carry out in those cities –

the way of navigating the city, meeting,

working, accessing knowledge – will be

tremendously different.”

■

Composite map of

the recorded traces of

trash type presented by

Professor Carlo Ratti and

his Trash Track team from

the SENSEable City Lab

at MIT.

| PEOPLE FLOW

8