race.” In a similar way, over the past

decade, digital technologies have

begun to blanket our cities, forming

the backbone of a large, intelligent

infrastructure.

At the heart of smart cities are intel-

ligent buildings. These are buildings

which contain systems which talk to each

other and are able to sense and respond

to different factors, such as changes in

the weather and in levels of occupancy.

Technology as liberation

But are smarter cities inherently more

livable cities? “In the end all of this is

not about technology,” says Ratti. “It’s

about how technology can help us live

in a different, more flexible way. Five or

ten years ago we were chained to a desk

or computer and couldn’t move. This

is about how can we use this liberating

power of technology to live or work in a

better way.”

Top down or bottom up

Pollalis believes the only way to create

a truly smart city is from the top down:

provide the infrastructure and the

operating environment to enable the

applications to enhance quality of life.

He was the concept

designer of the infor-

mation infrastructure

in the new administra-

tive city Songdo, in

South Korea. It was

dubbed the “happy

city” before the foun-

dations had been

laid, by Koreans who

assumed the people

living and working in

the eco-friendly, high-

tech community would

be happier. Opened in

2012, and expected

to house half a million people by 2030,

political wrangling led to the EUR 15

billion project being scaled down.

Other high-profile new smart cities

include Masdar in Abu Dhabi, which is

built on a huge podium, with the smart

infrastructure underneath, including

magnetic lanes for self-driving cars. All

the big top-down smart city projects

have run into difficulties – political,

financial or simply a lack of people

wanting to live in them – which is

perhaps not surprisingly given their

ground-breaking nature.

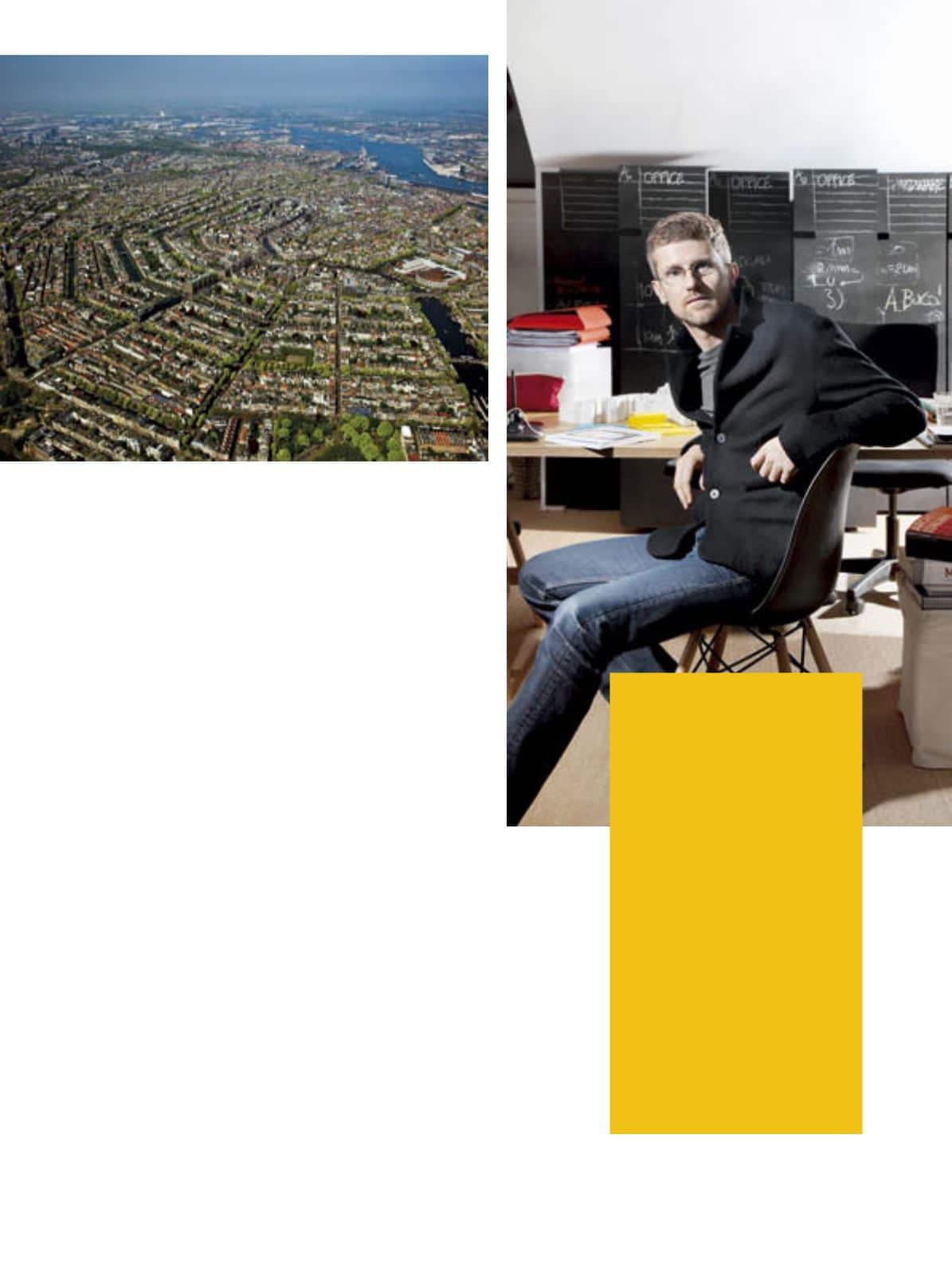

An architect and engineer by

training, Professor

Carlo Ratti

practices in Italy and teaches at

the Massachusetts Institute of

Technology, where he directs

the SENSEable City Lab. His

projects range from a digital

water pavilion in which all the

walls are “made from” running

water, providing a flexible, multi-

functional space, to tracking the

volume and frequency of phone

calls made between different parts

of the world to produce a better

understanding of the production

and flow of information between

global networks of cities. His work

has been exhibited worldwide

at venues including the Venice

Biennale, the Science Museum

in London, and the Museum of

Modern Art in New York.

The Dutch capital has set up the Amsterdam Smart City initiative,

a good example of an existing city getting smarter.

➝

7

PEOPLE FLOW |